How to Help Late Talkers: Activities for Parents and Caregivers

When toddlers are late to start talking, many new parents may wonder whether their children are hitting appropriate communication benchmarks and if they should worry about more significant developmental delays. While it is never too soon to seek a professional opinion from a speech language pathologist about a child’s speech development and language development, there are interventions parents and caregivers can implement at home to help children build communication skills.

“I hear parents say, ‘Oh, I tell them to go watch a movie or give them a tablet while I go cook,’” said Lauren Hastings, CCC-SLP, an Atlanta-based speech language pathologist. “You’re missing a whole opportunity to facilitate communication.”

Everyday activities like mealtime, errands and reading present opportunities for parents and caregivers to help their children build communication skills. Read on for resources that may help parents encourage their children to speak. To learn more about how children’s communication skills typically develop, check out the “Communication Milestones in Young Children” section, and continue below for tips and activities parents and caregivers can use to help children communicate.

Speech and Language Delays Verses Disorders

According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), late language emergence (LLE) is “a delay in language onset with no other diagnosed disabilities or developmental delays in other cognitive or motor domains. LLE is diagnosed when language development trajectories are below age expectations. Toddlers who exhibit LLE may also be referred to as ‘late talkers’ or ‘late language learners.’”

Risk factors for late talkers include a family history of language delay, sex (male) and lower birth weight.

Children with LLE may have both expressive language delays (delayed vocabulary acquisition, sentence structure development and articulation) or mixed expressive and receptive language delays (delayed oral language production and language comprehension).

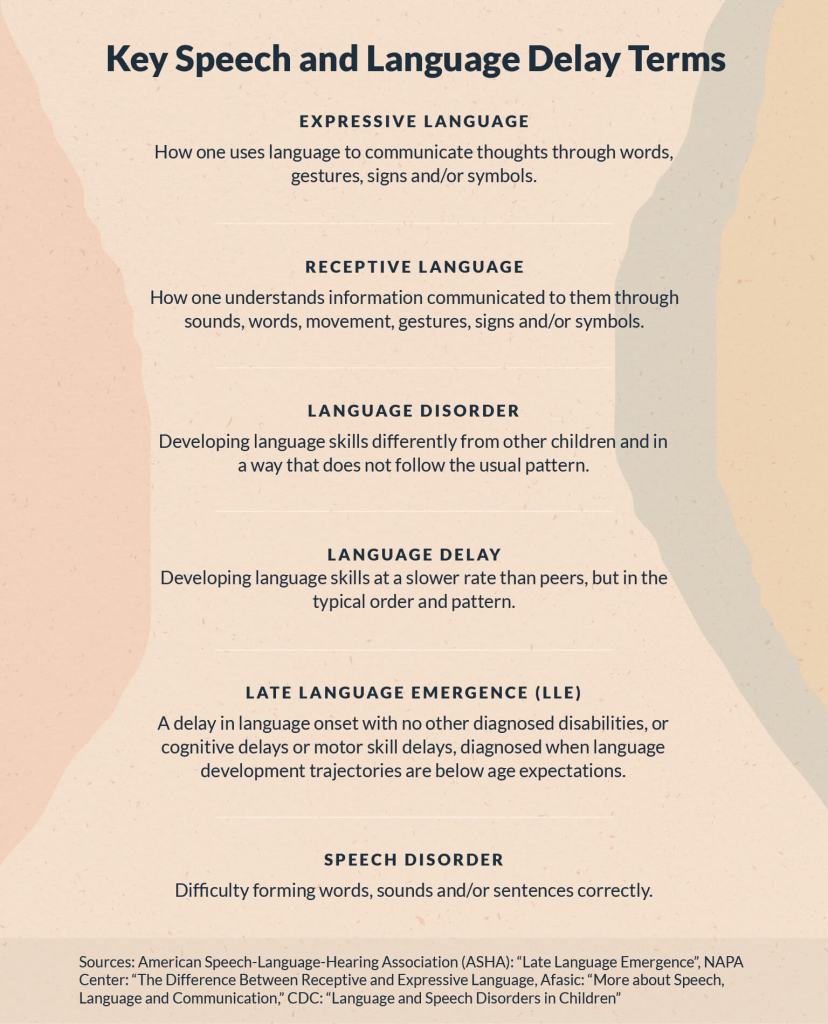

The above image shows key speech and language delay terms.

Running text:

Expressive language: how one uses language to communicate thoughts through words, gestures, signs and/or symbols.

Receptive language: how one understands information communicated to them through sounds, words, movement, gestures, signs and/or symbols.

Language delay: developing language skills at a slower rate than peers but in the typical order and pattern.

Language disorder: developing language skills differently from other children and in a way that does not follow the usual pattern.

Late language emergence (LLE): delay in language onset with no other diagnosed disabilities, cognitive delays or motor skill delays; diagnosed when language development trajectories are below age expectations.

Speech disorder: difficulty forming words, sounds and/or sentences correctly.

Sources:

Being slow to speak does not always indicate a child has a communication or developmental disorder, and some children will catch up to their peers. However, children with LLE may be at risk of developing other language or literacy issues, such as social communication disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual or learning disabilities, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), according to ASHA.

“Early intervention is critical because it prevents problems with behavior,” said Diane Paul, PhD, CCC-SLP, CAE, director of clinical issues in speech language pathology for ASHA. “If the child is frustrated by not being able to communicate, there may be behavior problems, social skill problems, and problems with reading and writing.”

Children with language delays or disorders may develop behavior problems out of frustration if they cannot be understood, understand what others say, convey their needs or have their requests met, Paul said. And because oral language is the foundation for written language, problems with early language comprehension or production can cause trouble with reading, writing and academics later in life.

Language delays can also affect children’s friendships and social lives.

“It’s difficult for children with language difficulties to approach other children; enter play groups; take turns in conversation with peers and adults; and initiate or respond to overtures from peers, which then makes it difficult to establish friendships,” Paul said.

Communication Milestones in Young Children

Children reach communication developmental milestones at different times, but it can be difficult for new parents to resist comparing their child’s development to that of their peers. Such comparisons are not useful, especially if their peers are precocious, Paul said.

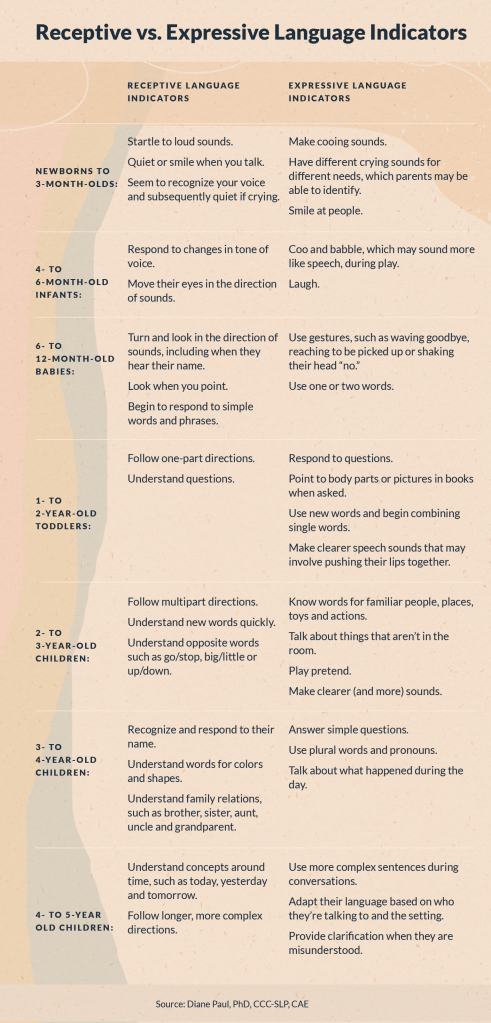

The above image shows receptive and expressive language indicators in children.

Running text:

Paul offered up these communication benchmarks typical for children of different age groups:

Newborns to 3-month-old babies have their hearing checked for problems, make cooing sounds, cry (parents may be able to identify different crying sounds for different needs) and smile.

4- to 6-month-old infants respond to changes in tone of voice; move their eyes in the direction of sounds; coo and babble, which may sound more like speech, during play; and laugh.

6- to 12-month-old babies use one or two words, use gestures such as waving goodbye, reach to be picked up and shake their head “no.”

1- to 2-year-old toddlers follow one-part directions, understand questions, respond to questions, point to body parts or pictures in books when asked, use new words and begin combining single words and make clearer speech sounds that involve pushing their lips together.

2- to 3-year-old children follow multipart directions; know words for familiar people, places, toys and actions; talk about things that aren’t in the room; play pretend; and make clearer sounds.

3- to 4-year-old children understand concepts around time, such as today, yesterday and tomorrow; follow longer, more complex directions; answer simple questions; use plural words and pronouns; and talk about what happened during the day.

4- to 5-year old children recognize and respond to their name; understand words for colors and shapes; understand family relations, such as brother, sister, aunt, uncle and grandparent; use language for multiple purposes, including greetings, asking questions, responding to questions and giving instructions; adapt their language based on who they’re talking to and the setting; and repeat what they previously said.

When to Involve an SLP

If a child is not meeting communication milestones, it can be hard to know definitively whether he or she is a late bloomer or has a more serious language or development problem.

Paul looks at the whole picture and how the child is developing in other areas. If the child is not meeting milestones in other areas, such as motor skills and cognition, that may indicate an overall developmental delay, Paul said. But if a child is meeting or exceeding other developmental milestones, it could be a “tradeoff.”

“A child who’s meeting the physical milestones and walks early and is running at age 12 months—that may be their strength and they’re going to come along with the language development milestones, too, but not in as quick of a way,” Paul said.

“Effective communication is really the essence of what makes us human. By paying attention to the milestones and focusing on encouraging speech and language skills, you’re really helping them become part of the human community.”

Paul always asks parents how well children are understanding them.

“If a child has good comprehension skills or receptive language skills and the parent says, ‘They understand everything I say,’ that’s a really good sign that their expressive language is going to follow a typical pattern,” Paul said.

If a child cannot perform comprehension tasks or answer simple questions (who, what, when, where, why or how)—even without talking—that can signal a more serious problem, said Hastings, the Atlanta-based SLP and owner of the speech therapy practice Hear to Speak, LLC.

“That’s how you know it’s more than just expressive language,” she said.

Toddlers may have a developmental problem if they:

- Do not understand what others say.

- Aren’t gesturing by 12 months of age.

- Favor gestures over words at 18 months of age.

- Won’t imitate sounds by 18 months of age.

- Shy away from attempting new words.

Sources:

Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego: “Delayed Speech or Language Development”

ASHA: “Late Blooming or Language Problem?”

Both Hastings and Paul encouraged parents not to wait and see if their child will grow out of a suspected problem.

“Parents should trust their judgement,” Paul said. “If you’re really not sure, the worst that can happen is you’ll get confirmation that your child is just fine.”

How Speech Language Pathologists Can Help Late Talkers

It’s never too soon to have your child evaluated because early intervention is critical to heading off speech language problems.

“Speech language pathologists can supplement what the parents are doing,” Paul said. “They can help with parent coaching, and they can really encourage speech and language stimulation to be a part of your everyday experience.”

An SLP can evaluate your child to see how well they understand, speak and use gestures if you think your child might have a problem. Having your child’s hearing tested can also help rule out or confirm if a hearing problem is contributing to their speech or language delay.

How Parents Can Encourage Communication in Late Talkers

Parent and caregiver interactions with late talkers help children develop their communication skills and supplement formal child speech therapy sessions with speech language pathologists.

“That is the continuation of the therapy plan,” Hastings said. “It’s important for the therapist to tell the daycare teacher and the parent so that they carry that over because then you will get a kid who will only do these things for the therapist.”

These tips may help parents and caregivers engage more effectively with late talkers:

- Model good speech, but don’t criticize your child’s speech if it is not perfectly clear.

- Imitate the sounds and words your child makes.

- Speak slowly so that a child can understand each part of a word.

- Listen and respond to your child even if they do not speak in full words or sentences.

- In bilingual households, talk to your child in your primary language.

- Pay attention to what a child says and not how they say it. Use many different words to help develop vocabulary.

- Follow your child’s lead by talking about things that catch their attention.

- Limit technological distractions and reduce screen time.

“Language learning is just a natural part of a child’s life,” Paul said. “Effective communication is really the essence of what makes us human. By paying attention to the milestones and focusing on encouraging speech and language skills, you’re really helping them become part of the human community.”

Activities for Parents and Caregivers to Help Late Talkers Communicate

SELF-TALK AND PARALLEL TALK

Narrating what you are doing and what your child is doing throughout the day provides ample opportunities for parents and caregivers to model good speech and conversation.

“I tell parents: Be a commentator of your life. ‘Oh, we’re home now? OK. Put up your stuff. Mommy’s going to make some dinner. Go grab your chair, and sit right here. We’re going to need a plate,’” Hastings said. “If the child is 6 months old—still do it.”

USE SIGNS

Pairing self-talk with sign language for basic needs can help children express themselves, and there is no research to suggest that using signs negatively affects a child’s speech and language production, Paul said. Signs are a form of expressive language, and they can help young children who are still learning to convey their wants and needs.

Using signs for “more,” “please” and “all done” will get you a long way, Hastings said. “It kind of covers all three important communication exchanges that parents have with their kids.”

PLAY

Playing games such as naming body parts, using building blocks, having fun during mealtimes and role playing can help children develop communication skills.

“You are teaching them about communication, about vocabulary, about conversation skills, storytelling, the sound and rhythm for language. And the context for their learning is play,” Paul said.

EXPANSIONS

Add one word to the words and phrases your child is using to help them learn to string together longer sentences.

“Let’s say you have a 3-year-old that still is just saying one-word [sentences]. Add one more. So if they know the word ‘cookie,’ [say] ‘more cookie,’” Hastings said. “They don’t have to repeat it, but expose them to it. Once they say it, you say it right back to them.”

READING

Start reading to a child every day from the time they are born.

“You don’t have to read every single word. You can talk about the story. You can talk about the pictures. You can encourage your child to tell a story,” Paul said. “That’s actually called dialogic reading where you’re reading together as a dialogue, creating the story based on the book.”

PANTRY PICTURES

Cut out pictures from snack boxes and put them on a board. Hastings suggested this strategy for one of her clients, who paired it with a picture that said “I want.” Now, instead of rummaging in the pantry, the child points to the snack he wants.

“If your kid is not talking or having trouble communicating, that can be a strategy or activity parents can use to help facilitate communication,” Hastings said. “Even if they are talking, that’s a great way to introduce vocabulary.”

Additional Resources for Parents of Late Talkers

- ASHA: How Does Your Child Hear and Talk?

- ASHA: ProFind

- Council for Exceptional Children: Division for Communication, Language, and Deaf/Hard of Hearing

- Council for Exceptional Children: Division for Early Childhood

- Friendship Circle: Eight Ways to Build Language and Communication Skills for Late Talkers

- The Hanen Centre: How to Tell If Your Child Is a Late Talker—And What to Do About It

- ASHA: Identify the Signs of Communication Disorders

- KidsHealth: Delayed Speech or Language Development

- Mayo Clinic: Language Development: Speech Milestones for Babies

- NAPA Center: 5 Great Language Development Activities

- National Association for the Education of Young Children: Communicating With Baby: Tips and Milestones From Birth to Age 5

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders: Speech and Language Developmental Milestones

- Speech Therapy Talk Services: Activities for a Late Talker

- Understood: What Is Child Find?

Please note that this article is for informational purposes only. Individuals should consult their healthcare provider before following any of the information provided.